Inktober 10/13: Time Pieces and Graphs

Ethan Reed

Hello all - three more images for Inktober.

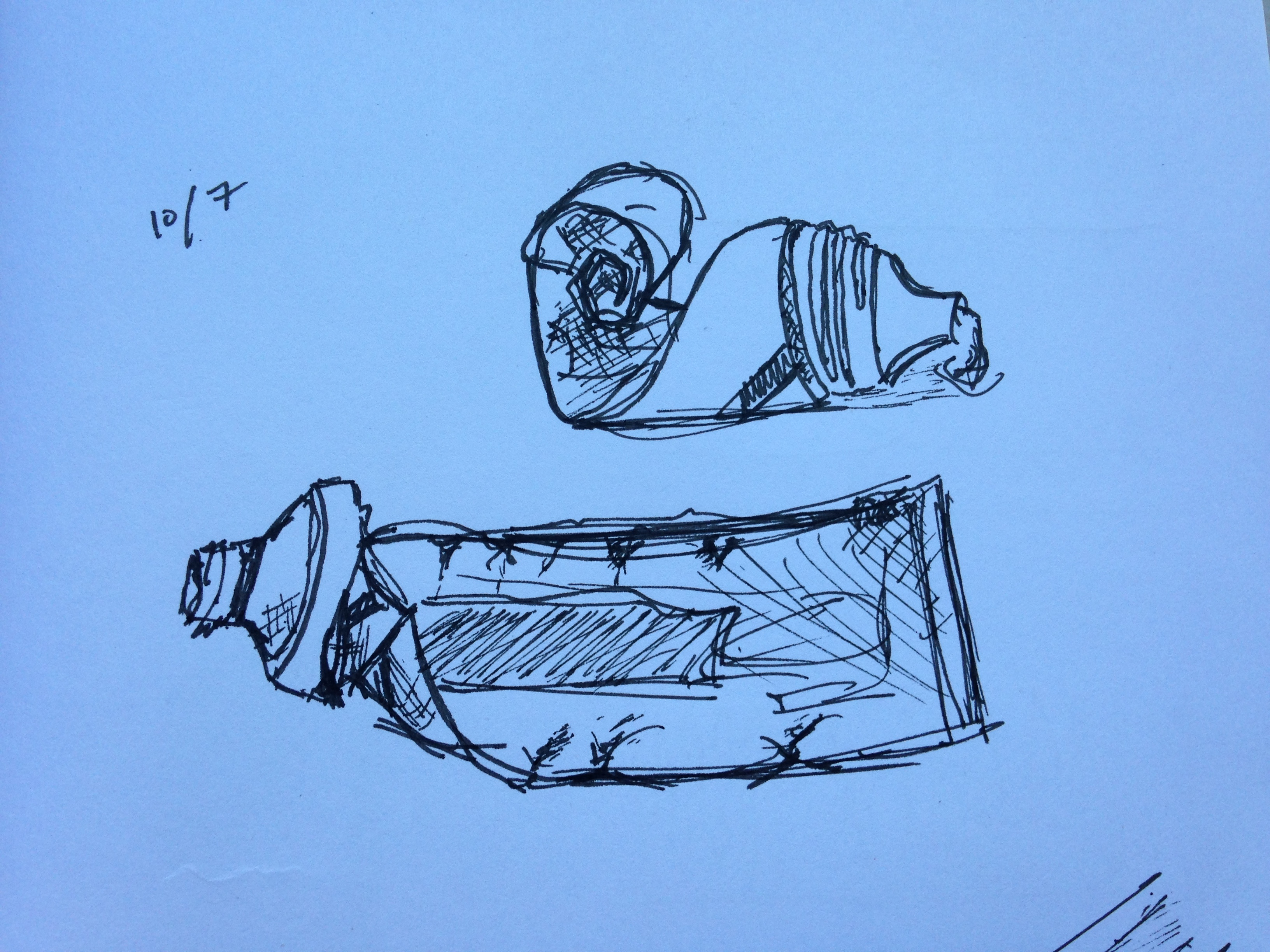

The first is a continuation from my previous Inktober post, very simply, two tubes of toothpaste, both almost empty.

Was still thinking of the consumption of objects, for two reasons: first, because of their importance to a historical thinker deeply interested in time (and on my orals list), one Karl Marx, who writes on everything from the length of the working day to labour-time itself here in the first chapter of Capital. And second, because a lot of people use toothpaste in their everyday life. It is something they consume very slowly, and often even forget that they have or that it’s running out; they measure out its consumption bit by bit over the course of many weeks, but its presence over time is ‘at hand,’ or taken for granted in a certain way.

To start with Marx though, in the first chapter of Capital (titled: Commodities) he defines the value of a commodity as “the labour time socially necessary for its production.” He then goes on to quote himself from the Economic & Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 saying that “As exchange values, all commodities are merely definite quantities of congealed labour-time.”

What a phrase! Congealed labour-time. As though the object in hand were physically made up of hours from the lives of others. The idea that an hour of life itself can be estranged from an individual and sold for monetary compensation, and that these hours of others then congeal into an object which sits on my bathroom sink for a set number of weeks is fascinating, and which Marx thinks through seriously, though too much to talk about here.

My second point though, that people use toothpaste everyday, has to do with the thinking of another philosopher I’ve been reading while studying for my oral exams - Martin Heidegger. Though he’s interested in his big work about ontological questions (like, what kind of being does the number 1 have vs. the color brown, a chair, the solar system, a historical event, my cat, etc) he also believes that things ‘are’ for humans (or Dasein in his terminology, the being for whom being is an issue or question) in a way that is more natural. In his thinking, when I see a desk, I don’t go for some abstract, philosophical, Aristotelian route and think of it as a substance with attributes (such as squareness or brownness), I think more of whether or not it is the right size, or close enough to a reading light, or if it is an heirloom that needs to be treated carefully. That these considerations actually make up, in many ways, the ‘being’ of the table itself for Dasein (humans) was fascinating to me when I first started reading.

Hence: toothpaste! I brush my teeth twice a day and use toothpaste from a tube that looks like one of these. It is something that fits in my hand and I can tell how much time I have left with this particular tube just by picking it up. Using a brand new tube is very different from the ones I have drawn here, crumpling up tubes to try to make them last, to extend their lives. The “time” of a tube of toothpaste, its lifespan, is relatively slow (or long) compared to, say, a quart of milk or loaf of bread. The same tube persists through many weeks of use, and there is even a certain feeling of ‘letting go’ and beginning again when I have to stop crushing up an old familiar tube and go buy new. And trying a new brand, flavor, or type of toothpaste is a strangely serious time commitment, a decision that persists in your everyday experience (and teeth) for weeks or months.

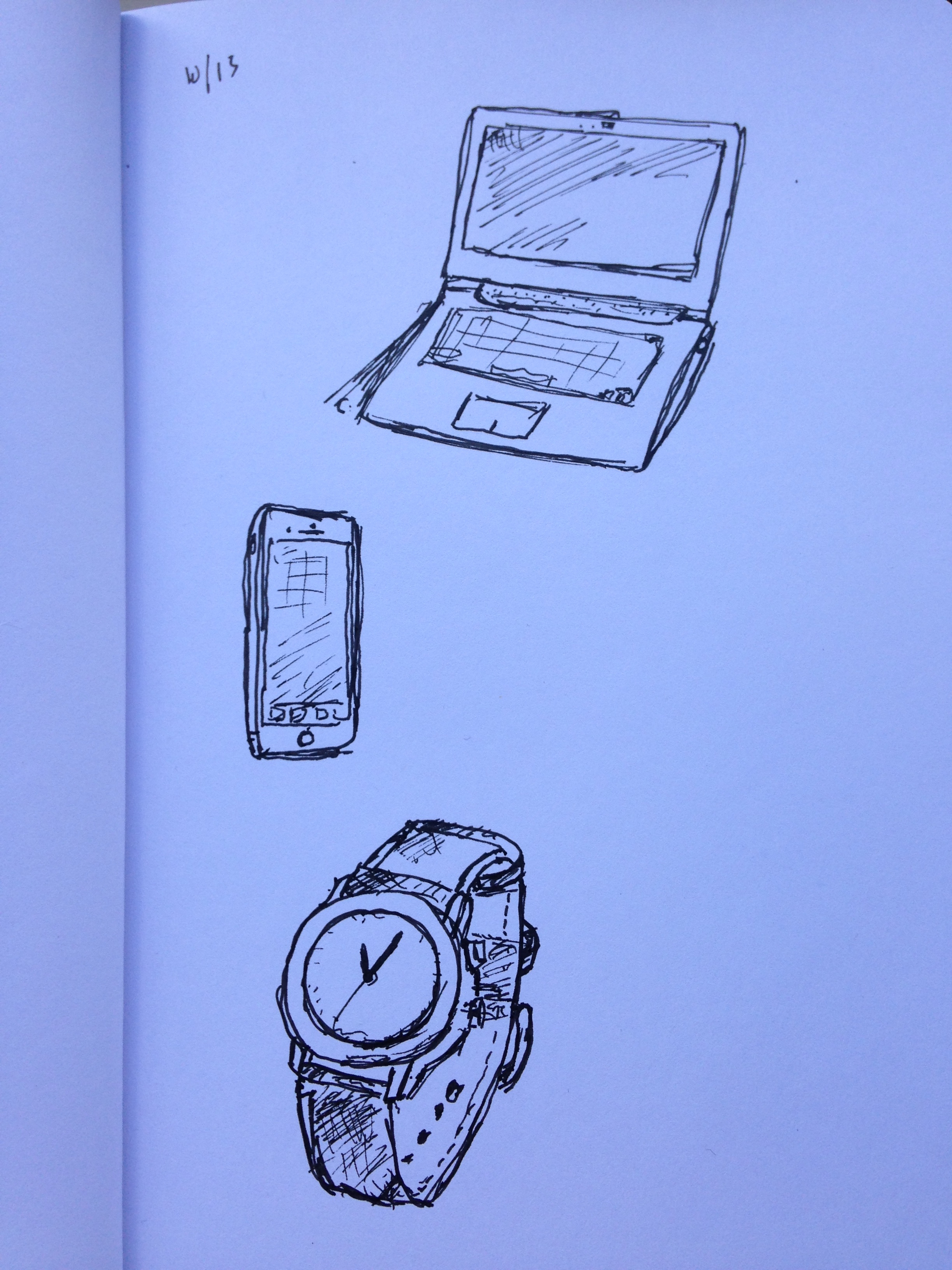

This connects with another picture, those of time pieces.

I wanted to draw the things I look at during the day to tell what time it is. When this Dasein thinks of time (me), he probably thinks first of where he looks to ‘tell the time,’ the things I use to make sure that I am not late, or that I am getting enough sleep, or that I remember to eat lunch. For me these are my computer and my phone. My window into Greenwich Mean Time is almost always small numbers on a screen that sometimes fail to update to Daylight Savings. A lot of people have watches though, so I wanted to draw one of them too. I wonder how these objects of mediators of this standard time influence how time actually feels for the humans who use them.

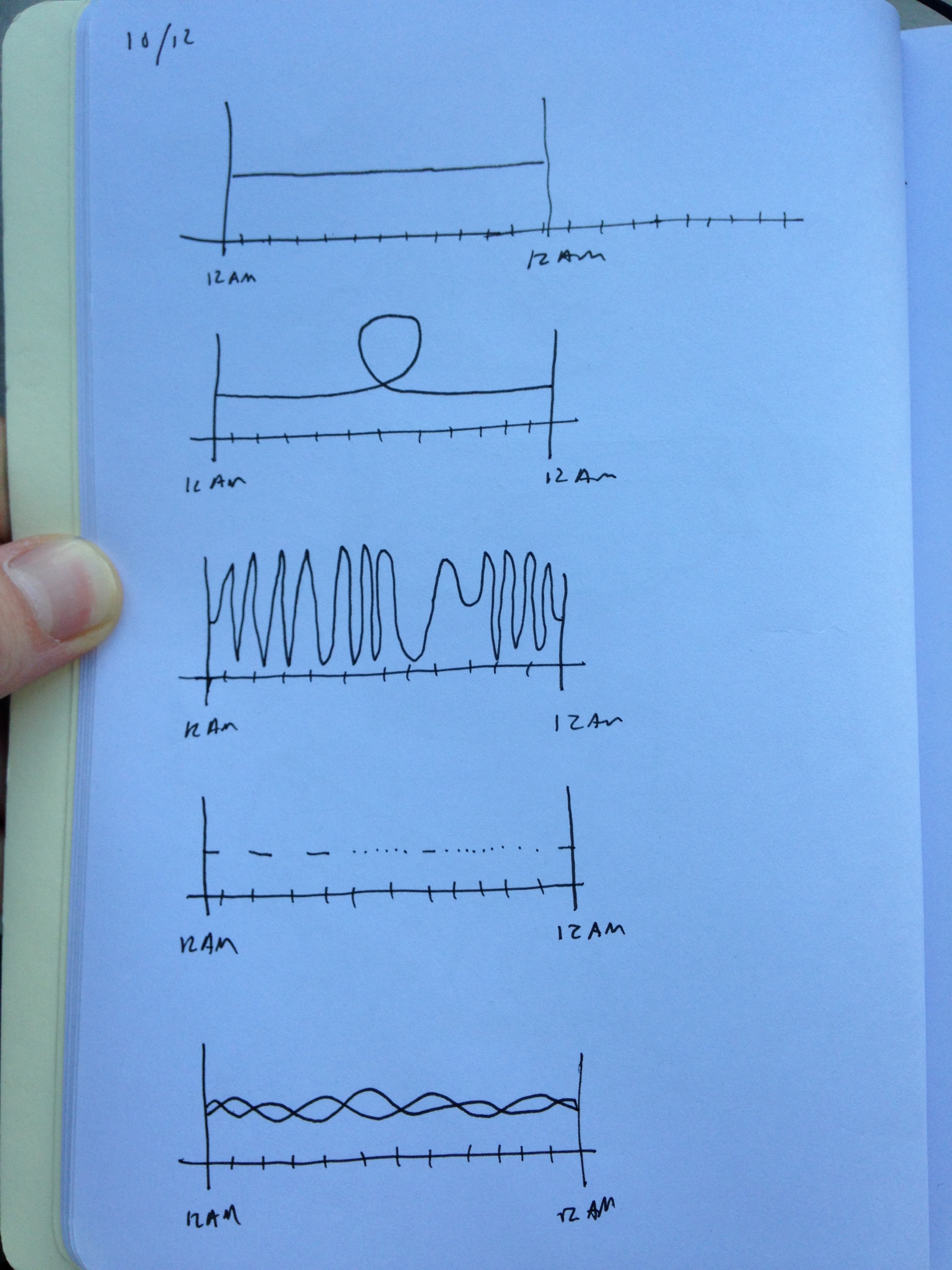

Last is more abstract. I was thinking of Johanna Drucker’s work in Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production, and particularly an article she wrote for DHQ called “Humanities Approaches to Graphical Display” in which she gives some examples of how humanists can use graphical representations. So I decided to draw some graphs about how we might experience time in a 24-hour period.

I was envisioning that a given person would travel along the path of the line, x-axis being each hour passing, and y-axis being… something else. Experience? Not sure - point being, although the same number of ‘hours’ passed for each line, the length, trajectory, and experience of each line (or sets of lines) was very unique. Would love to draw some more of these, or at least think through them a little more seriously before the month is out.