So, we’ve all been doing Inktober and I’ve taken a while to get up to speed. It seems to me that Inktober is aimed at “artists all over the world,” not so much writers, or writers of essays and dissertations. Many of my artist friends have worked hard to perfect their art and Inktober seems like a chance for them to show off their fabulous work. What have I been hard at work on that deserves to even stand alongside their hard-won skills?

In early October, I visited the Fralin Museum of Art and saw some of their selection of the I GOT UP conceptual art of On Kawara which struck a chord with me (sadly, they didn’t allow photography, but they’re pretty similar to the work that the Metropolitan Museum of Art has posted.) What struck me about Kawara’s conceptual art was that it was art in the doing, not in the singular action. He produced a process that of writing and mailing postcards all around the world, stopping only when his stamp was stolen. If it’s about nothing else, Inktober is about commitment to process and On Kawara seemed like as good an emblem as any.

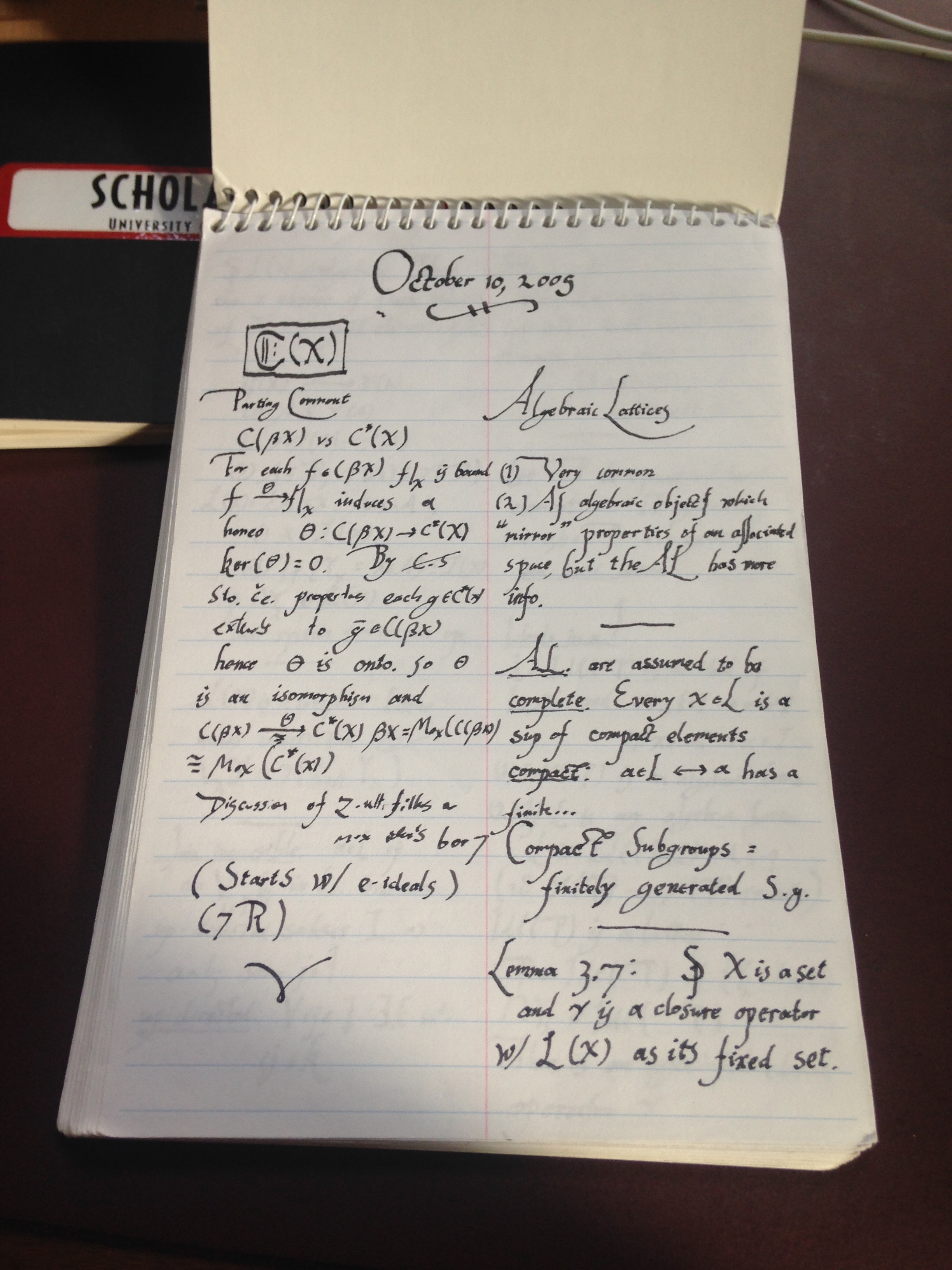

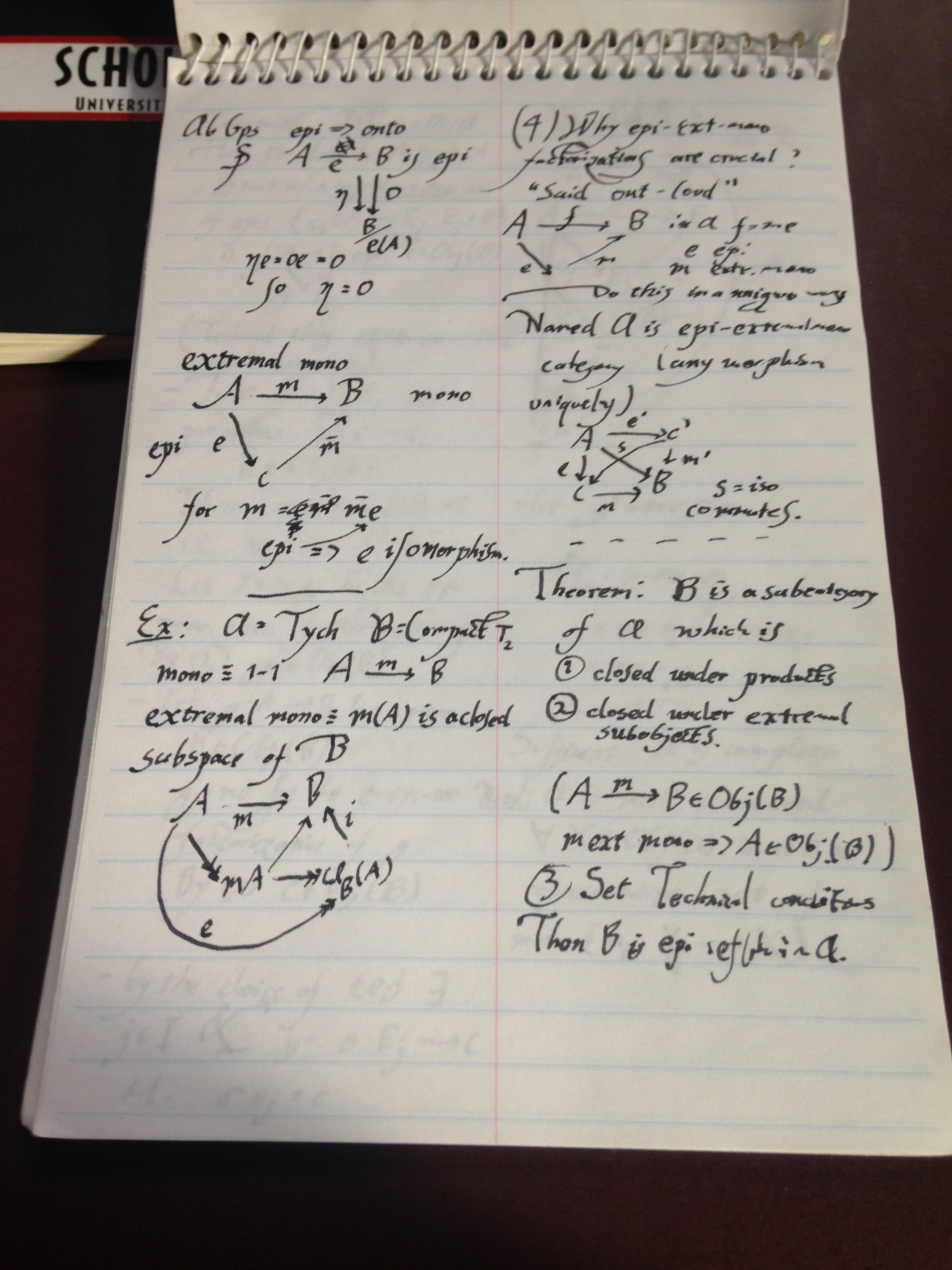

Ten years ago in October, I was at the University of Florida in my last year of coursework and taking notes for my classes. My handwriting had always been atrocious and I often couldn’t read my own notes, so I decided to improve it. My friend Justin Smith and I had spent the summer leaning a running italic hand from a copy of Ludovico Vicentio degli Arrighi’s La Operina that we had found in facsimile (we had to stumble through with an Italian dictionary in hand, but you can find a free translated version online which is quite nice.) By October 10th, my handwriting had greatly improved even though my notes looked a bit silly:

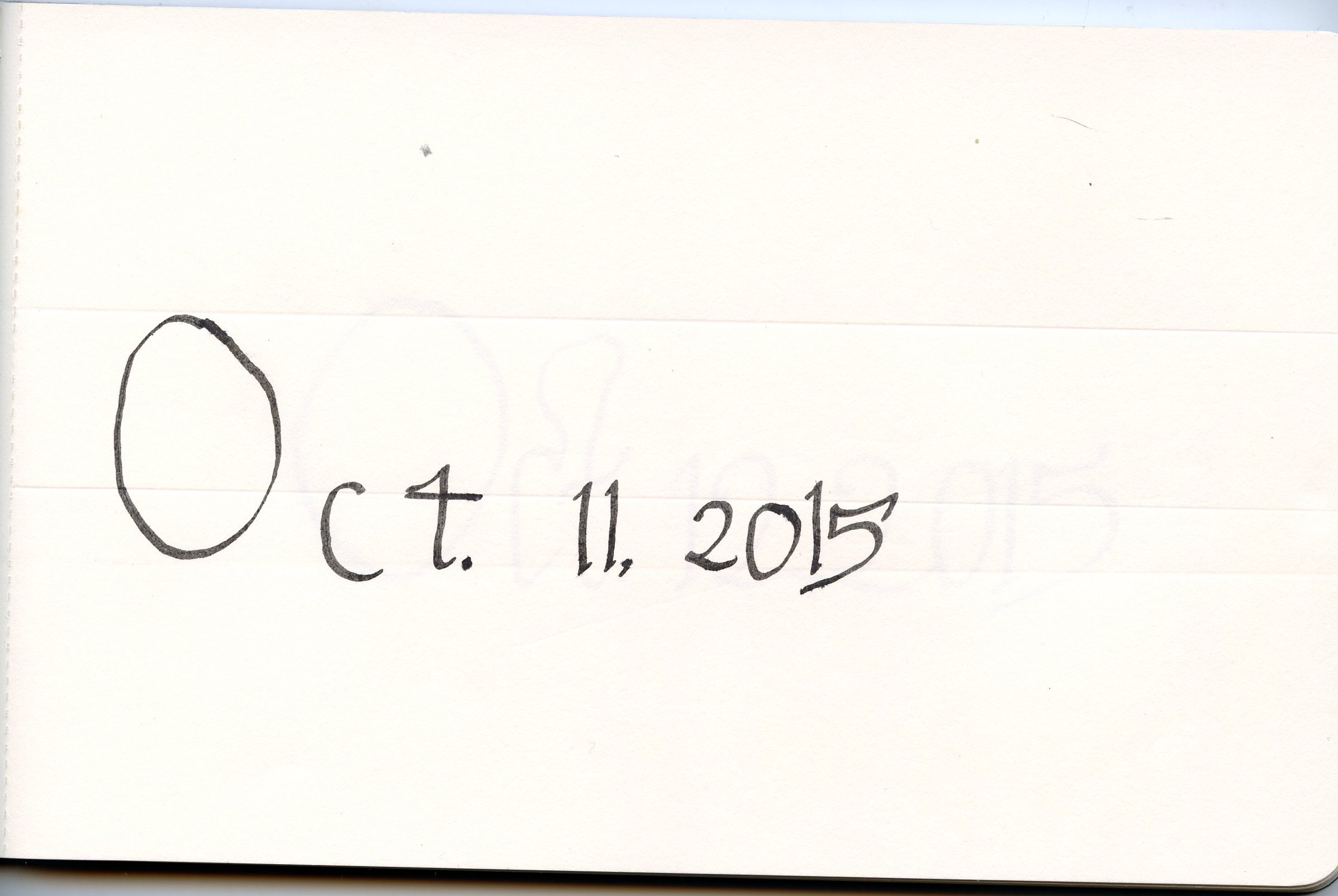

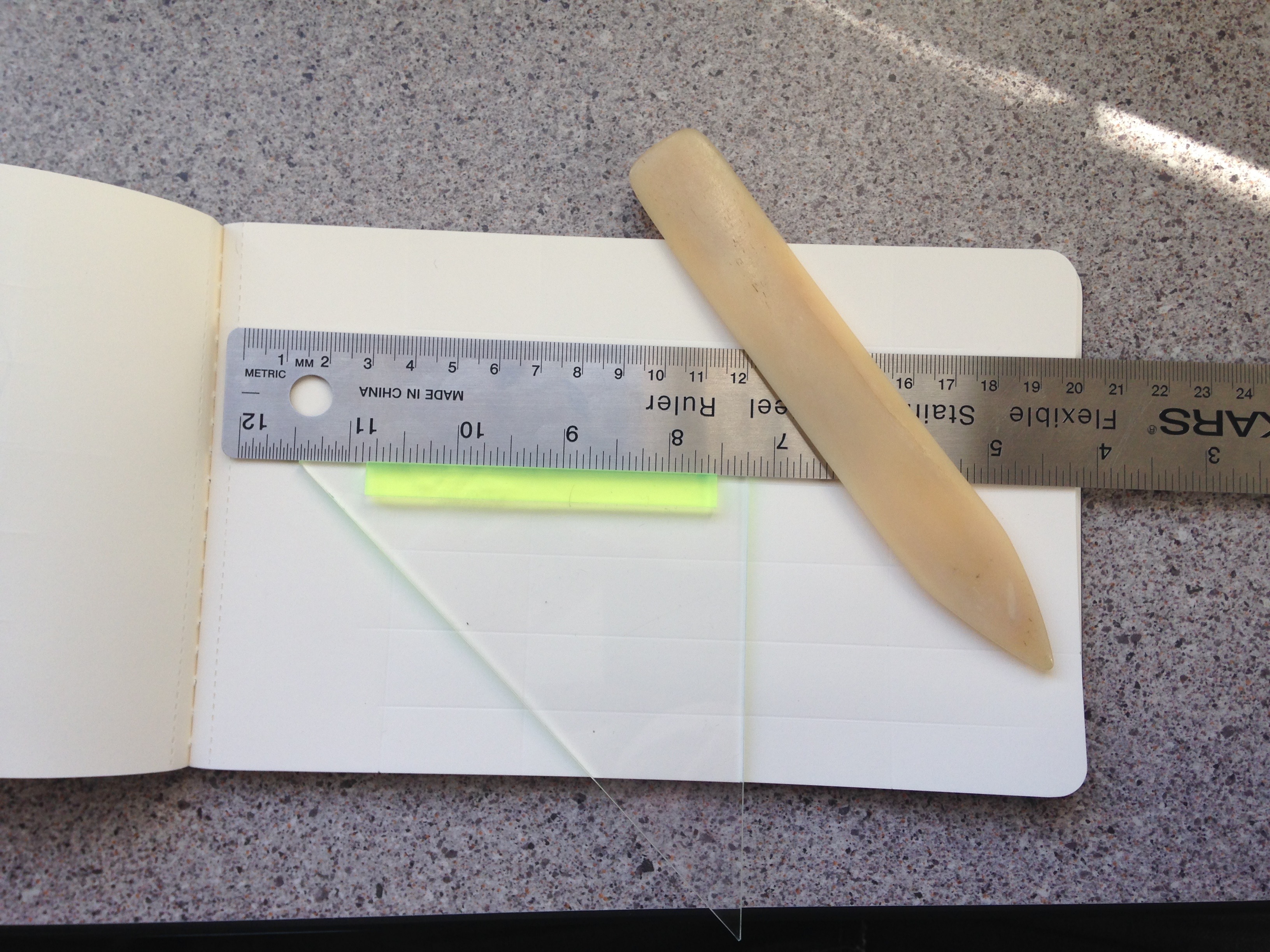

It seems to me that this Inktober was a great time for me to practice writing, thinking about time, and coding metadata. Starting with just ruling some lines to guide my writing with a bone folder and straight-edge, I began by writing the date:

The horizontal rules from the previous page had pushed through to the next, which saved me time as I could line the ruler up on these previous lines. However, I didn’t like how October 11th was too far to the left, so I measured the width of the date, the width of the page, and ruled two more lines to make it centered:

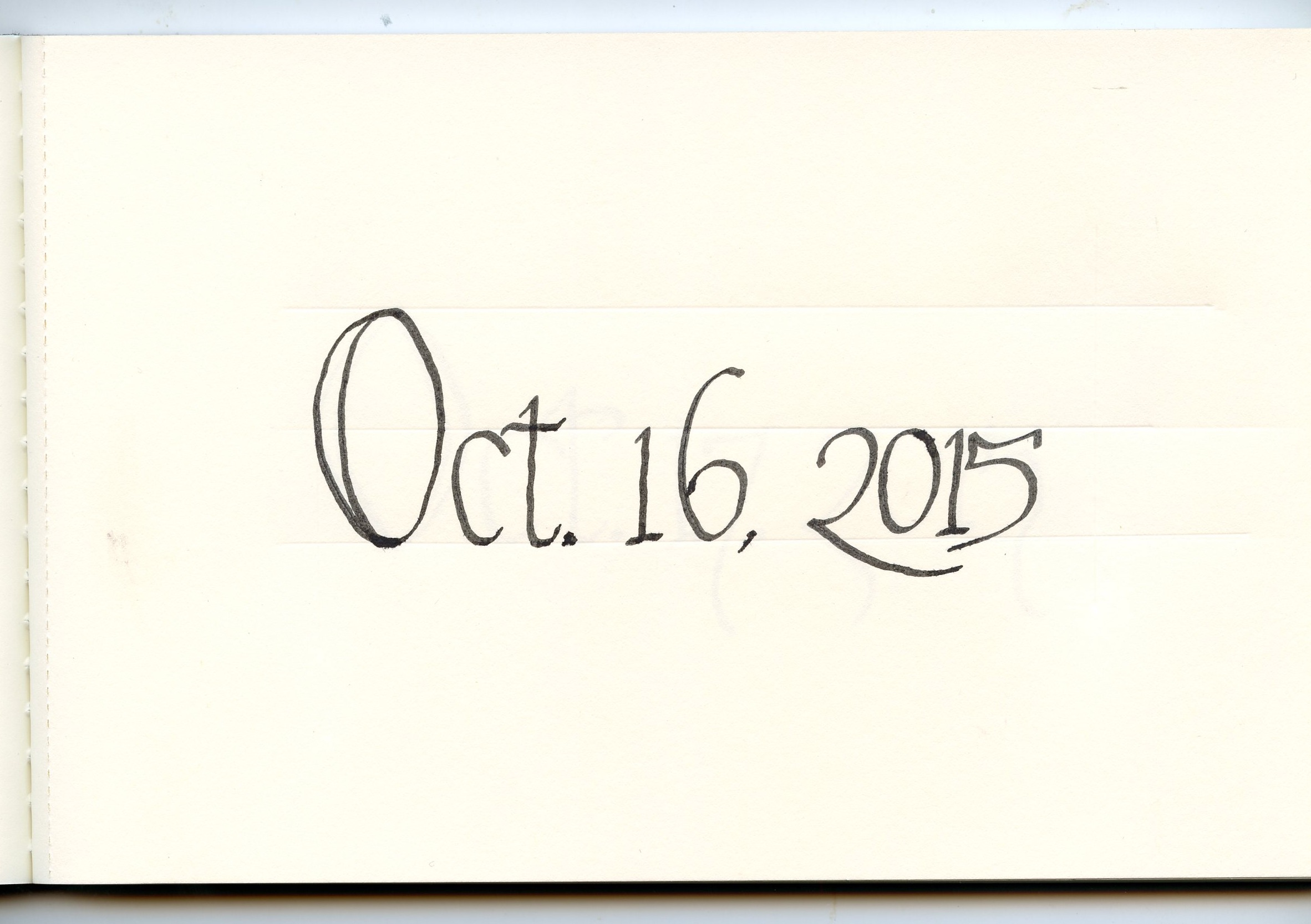

I kept up this procedure, varying the ruled but uninked lines—which carried through the paper to the next day—and trying to perfect a sort of graphic representation of the date. Looking back, I think by October 16th I had achieved a stable clarity:

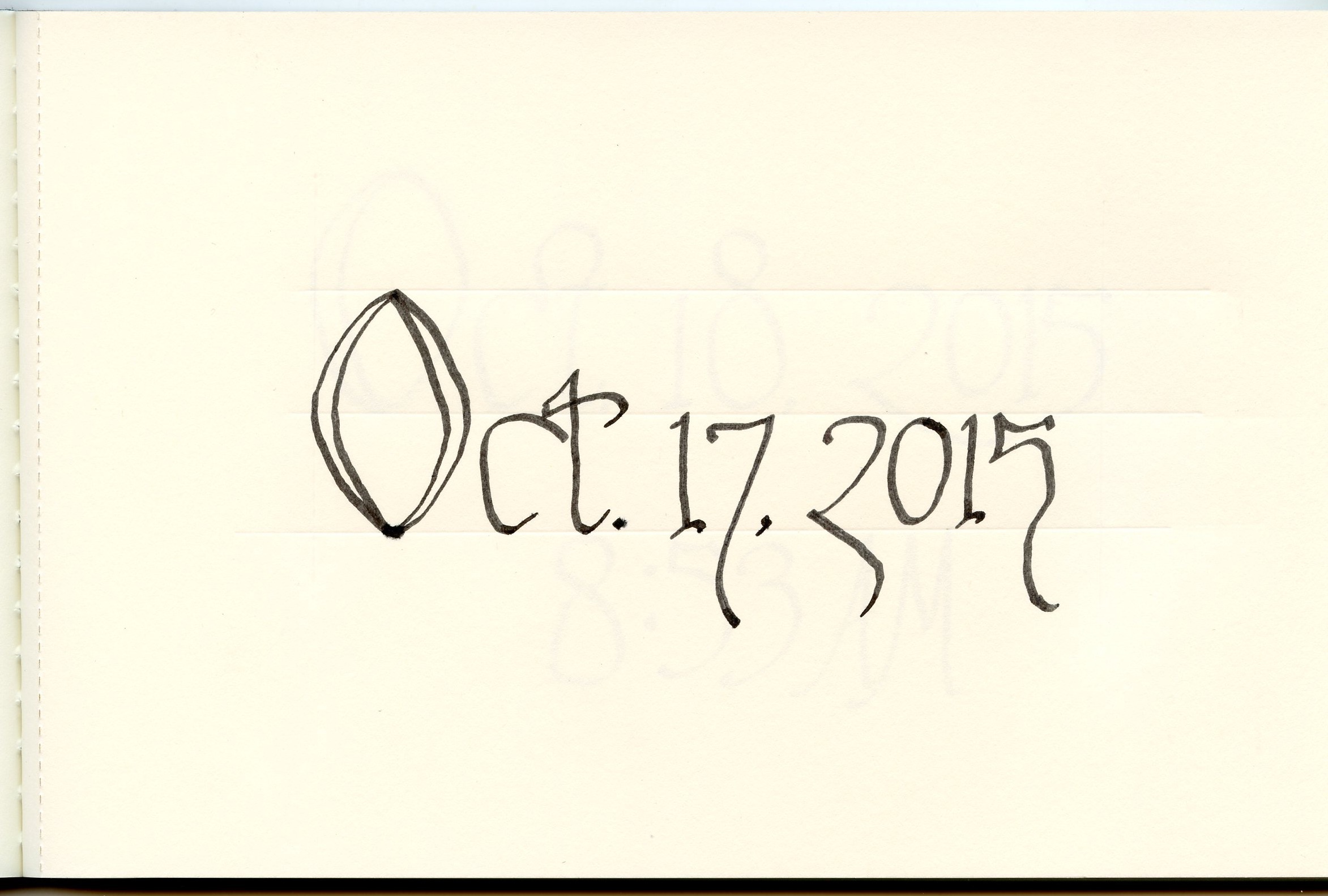

Which, of course, meant that on October 17th I slipped into an artistic period of decadence. You can almost hear some sort of Halloween plastic faux-skull laughing through these letters with their wildly and unnecessarily curving serifs:

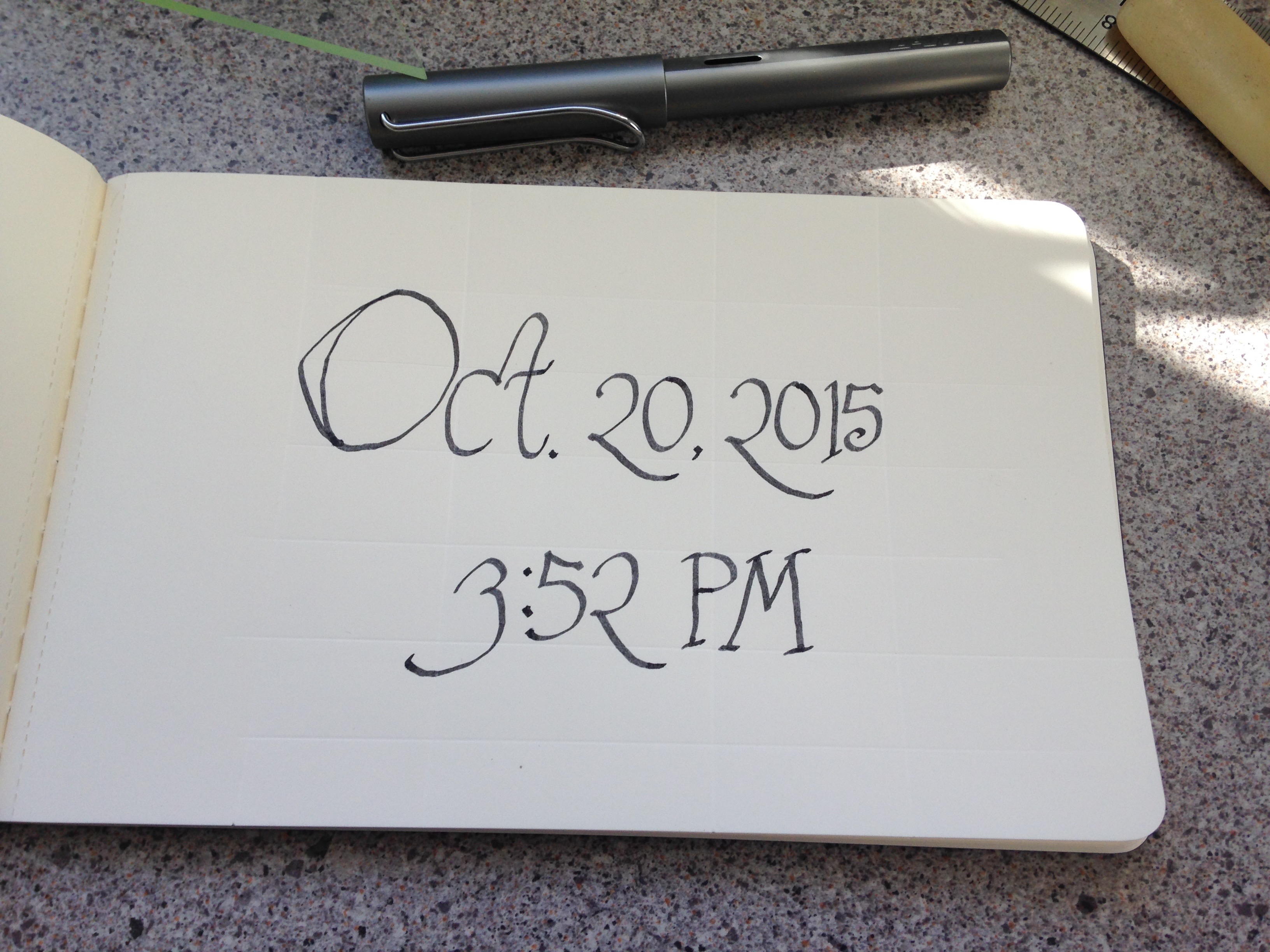

I needed something new and as we’ve been thinking about how time can be granular in different ways, I thought about the fact I was writing the day, but not the time. The drawing didn’t occur all day, it happened within a specific set of minutes at some point in the day, so giving it only a date seemed somehow disingenuous. I took the lines that were carrying through from the previous day and spent several days perfecting a layout for for the date and time. By October 20th I had gotten my system of ruling down and was satisfied with the layout:

My date and time from that day seems to be the clearest that I produced with that template, a smidgen of fancy in the five, but otherwise restrained and clear:

Looking back, I can now see the pattern where after the moment of clarity, I draw with decadence. October 21st was an attempt to capture the look of broken type on the ‘7’ while keeping the rest of the page as clear as possible:

Clearly, I needed a new challenge to keep going. Since this was my second time writing away from my desk at home, I figured I’d start to record the location where I did the drawing as well. I’ve not yet hit another moment of clarity yet: the location isn’t centered and looks too big, but I am pleased enough with the direction I’m headed that I’ve taken to posting my images to Instagram where strangers have begun flagging them with likes:

The Invisible Girdle as Layout

In our meetings, we’ve been talking about the concept of the “invisible girdle,” (coined by Rachel Trapp as a better version of “invisible corset” which described a series of invisible nodes and edges I was trying to use in my Graphviz visualizations of time to force the graph into a particular layout; Ethan Reed has suggested that “invisible” might not even be the right word and he’s undoubtedly posted on that by now) by which we mean both cultural and political constraints on how time functions. Our literature is girdled into centuries, nations, and languages; our parts of town are girdled into commercial, green space, car space, and bike space. Girdling is always suspect, though not always necessarily bad. There is a connection to Go-go dancing in Washington D.C. which Gillet has recently written about as well as Lydia in a previous post.

interest in the invisible girdle is that it is also a good metaphor for the process of layout and the history of body techniques. In the Inktober drawings above, my ruled lines form a sort of invisible girdle for unruled letters that extend to, and sometimes beyond, the girdle but are roughly kept in place. So, at a particular moment in time, the ruled lines create the layout for the drawing. However, the lines are carried forward from day to day.

When I rule October 25th, there will be the faint traces of the rules from October 24th that will help guide me in laying out the lines. This happens because my notebook is in codex form so when I rule one page, the effect of that ruling extends to the page below as well and someone even to the next page. The soft touch of a fountain pen on suitably sized paper doesn’t carry to the next page, but the pressure from my ruling does. For the way I’m thinking about the invisible girdle, this is a productive metaphor. An earlier girdle sets-up the condition for the today’s and even when you want to alter the layout, you cannot stray too far without obviously coloring outside of the lines. An invisible girdle from today, one from yesterday, and perhaps one even further back, constrains my unruly handwriting.

Cascading Style-Sheets and more modern internet layout technology build on this long history of layout as girdle. When we update the margins, the padding, the border, etc. of how an element will display on a page it gives it space to expand is some ways and constrains it in others. When we look to a technology like d3.js, we see data driven documents, that is the data flows into the document’s layout. When we program for d3.js, we decide on the girdle that some—perhaps unknown—collection of data will fit into.

Yet, these technologies hail their earlier incarnations in the same way that the ruling from one page of my notebook passes to another. Jaron Lanier reminds us in You Are Not a Gadget that internet technologies are the hack that suited a particular time petrified into an inherited practice. His example of MIDI as standard for data transmission, but profoundly tied to 80s keyboard synths, shows how our new technologies often have bits of the old within them.

As I write this in Emacs, a text-editor that chronologically could be my older brother, I think about how what we can do today is constrained by what we knew how to do yesterday. Yesterday’s limitations in Internet Explorer, limit HTML, which in turn limits the development of CSS, and constrain how we think webpages should look. It as though the past is present especially prominently in the hidden code of the most forward-moving technologies. Marcel Mauss explored a similar idea with body techniques, observing that the 1902 Encyclopedia Britannica described a way of swimming that few people continued to practice. We learn body techniques by mimicking the previous generation and so they change, but slowly. Different times and nations have different body techniques, but new ones can’t move far from where we are now.

Our digital invisible girdles that constrain not only what things can look like, but what we think they should look like, are a chaotic kludge hacked together from partially remembered pieces of the past. Ten years ago, I began to use italic handwriting for my notes to store information; naturally, today I turn to that same technique when asked to draw in ink.