So. I’m going to somewhat breathlessly throw some thoughts out there about time and the body. The other day I was putting on mascara and thinking about how women use makeup to alter the way that time appears on their bodies. Young girls often apply makeup to appear older, whether for fun or to gain access things reserved for older girls, or both (or neither). Then at a certain age, women learn from a variety of sources that they are supposed to apply cremes and makeup in order to stop the appearance of aging on the face and body. Wrinkles and laugh-lines show on our faces, gray hairs pop up, and the beauty industry wants us to stop it (with their help). Going down this particular rabbit hole got me thinking about time as a force which exerts pressure on us with particular somatic effects. The manifestation of this force, of course, varies from person to person and across racial/gender/class/etc. lines. For example, there have been many studies on poverty and its effect on the body. The stressors of poverty have been correlated to faster aging, shorter life expectancies, and a host of developmental differences/concerns. How then, do we represent time as an external force and stay attuned to the different force with which a particular unit of time may effect a given person or group of persons?

(Quick side-note: I spent a good couple of minutes talking with fellow Praxis-er Rachel about whether to use “effect” or “affect” when writing about time and the body. On the one hand, applying makeup is an affect that enables us to present the relationship between our body and time to the public in a particular way. Also, to say affect would also imply that we have some amount of agency in terms of letting stress age us more or vice versa. But then I realized that what I wanted to think about was more about the way that time has an effect on us and our bodies that in many ways is a function of forces beyond our control, like genes (though this itself is somewhat contestable?). So. There’s that).

On the other hand, many of us speak about time as something we do or do not have possession of. Time to work, to exercise, to eat, to sleep, to participate in leisure activities. Is there a way to represent time as something material of which we can claim possession? Is it possible to do this without thinking about the capitalist notion of time being money? What’s the relationship between thinking about time as a possession (or monetary value) and time as a force on and in our lives? To relate it to Scholar’s Lab developer Scott’s interests–how does not having time in the sense of having a terminal illness influence the passage of time within our bodies? Or how do our bodies and things happening within/to them influence our notion of time?

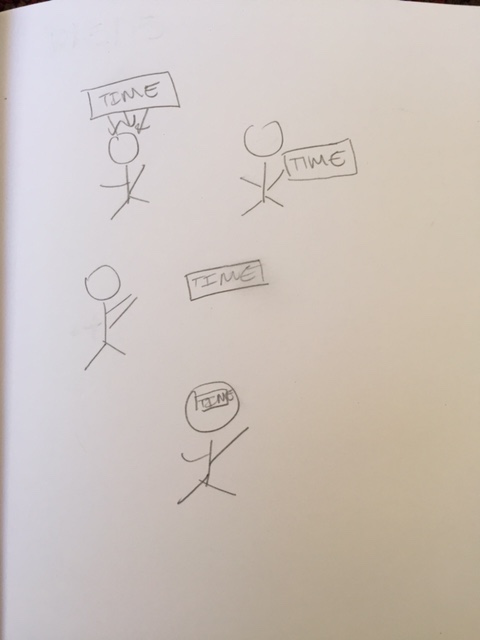

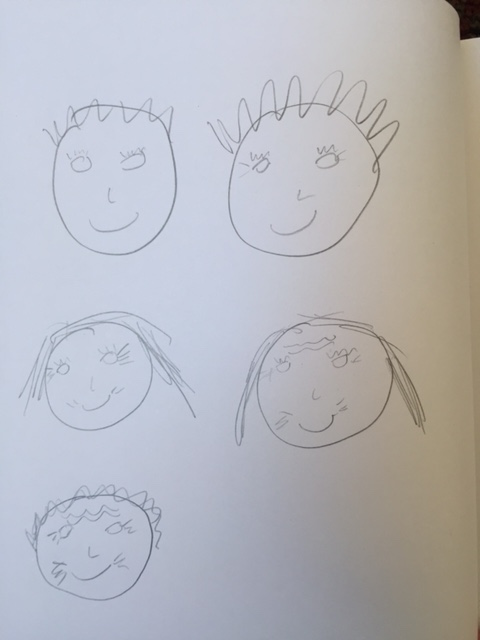

So these are two sketches that kind of get at the questions I’ve posed. :D